AN AUSTRAL SANDALWOOD

published on 2023-08-13Olfactory vision around Australian sandalwood (Santalum spicatum).

Interview carried out in the magazine of the profession “Perfumer & Flavorist” after the evaluation of the different materials offered by the company Dujhtan.

- What comes to mind when first experiencing the material?

There are materials, such as olibanum resin, popularized under the name “incense”, whose scents cross the minds and, throughout history, humanity.

Beyond all religious beliefs, sandalwood soothes your mind.

My first contemplation of its essential oil was during my training as a student perfumer in 2006 in Grasse.

The volatile extract invited me to these motionless journeys; not those who transport you in your memories; rather, those that bring you to the doorstep of your imagination.

Transcended by this new smell, my vision was nomadic like the flight of a boomerang over arid lands of dust and spices.

A common interpretation with that of Michel Roudnitska, imagined for his multisensory show “Un Monde en Senteurs” which I discovered during the 9th Perfume Day in Grasse in 2007.

This certainly contributed to my interest in olfactory scenography in the field of culture.

- How is this material sourced? Is it easy to find/acquire?

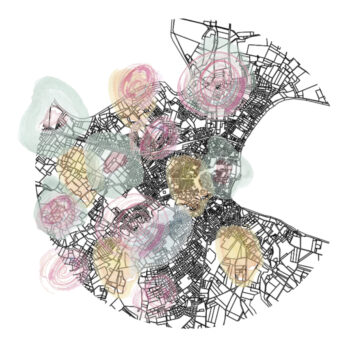

Santalum spicatum is native to the semi-arid regions of southern and western Australia.

It is the oldest living fragrant species of Santalum, said to be some 13 million years old.

Aboriginal people venerate this wood and crown it under the name of “Dutjahn”.

There are other species endemic to the largest country in Oceania, such as Santalum obtusifolium, lanceolatum, preissianum, murrayanum and acuminatum species.

The perfume industry essentially exploits three species of sandalwood (Santalum) with spicatum, album – native to India – and austrocaledonicum found in New Caledonia and Vanuatu.

Sources of many commercial exchanges, the austral sandalwoods (as I like to call them) have been overexploited.

In the 19th century, colonial frigates even bore the name “santaliers”.

They were loading their holds to barter it for tea.

In 1893, José-Maria de Heredia wrote in his book “The Conquerors of Gold”: The coast was lowering, and the sandalwoods exhaled their fragrant breezes over the sea”

Since the 1990s, people in Australia have been repairing and regenerating their forests.

- What have you used/what would you use this material in?

Guarantor of knowledge and an olfactory experience, the perfumer becomes a “scent-seï”.

When I was working for a raw materials and compositions company in Grasse, in the presence of my Japanese trainee, we were designing fragrances for incense typical of her country.

It was then necessary to integrate into the design of the finished product, sandalwood powder which, in addition to its smell, served as a fixed base.

Fragrant or architectural, this wood will serve as a scented framework for a perfume or a temple.

Over time, measure of luxury, the essential oils of this tree will refine a fragrance.

- Could you touch on this material’s versatility?

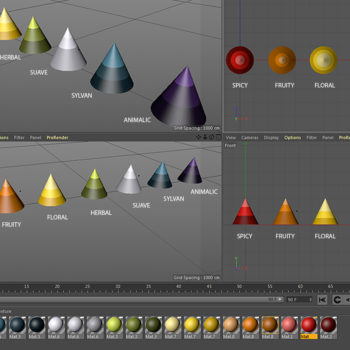

We know that the aromatic profile of the essential oil from the same plant varies according to numerous parameters: its geolocation, according to the soil, according to the meteorology, particularly the rate of precipitation, if the harvest comes from a plantation or if it is savage…

Regarding the essential oil of Australian sandalwood (Santalum spicatum), its versatility is deeply rooted in the different parts of the tree.

If we plunge our nose into the extracts of logs or roots, living or dead, the olfactory descriptors are differentiated.

For the logs, the smell is certainly rich and woody with phenolic accents, rubbery like guaiac wood, warm and spicy like nutmeg,

There is this empyreumatic sensation, vivacious as heated flint.

A certain minerality like that of gunflint aroma that we identify in certain Riesling, Chablis or Sancerre wines.

More puzzling is the bold, green, floral effect of a rose, just waiting to pair with the flower.

A certain dryness is often noticed in sandalwood.

These dry woody notes come from alpha-santalene, alpha-santalol and alpha-santalal molecules.

By distilling the roots and butts of the tree, they are made slightly more vetiver and much creamier.

At low concentrations, pyrazines are their charms, their intense odors cause effects of pepper, hazelnut or toasted sesame.

Another discovery is that of the essential oil called “Desert Dry”.

It would be logical to think that after the death of a living being, its soul releases.

However, the essence is present when distilling this oil from “dead wood” harvested from wild trees that have existed for years in the desert.

- In what types of formulations could it be used as a star? Or even as a supporting role?

These multiple facets make Australian sandalwood (Santalum spicatum) an inexhaustible source of inspiration for the perfumer-creator.

Sandalwood enhances floral accords.

It gives voice to silent flowers like lily of the valley, with which it shares the same molecule: iso-beta bisabolol.

Invisible to the nose, with its heart, the essential oil takes care of your roses and touches them.

By co-distillation to obtain the attars, it infuses them in an archetypal accord.

In the various scent composition Santalum spicatum, much like Amyris balsamifera, has often been given a secondary role, mainly replacing Indian sandalwood, Santalum album.

Historically, many of us perfumers have found this essential oil too racy, but new processes allow us to carve this wood, to refine it.

By eliminating hydrocarbon compounds and others, fractional distillation will reveal santalol, this fraction of various alcohols such as vetiverol for vetiver.

Far from being a substitute, Australian Sandalwood is a lover, an exalter that brings other materials to the top.

Its exquisite complexity reveals new and unprecedented accords

- Is this material reminiscent of anything you’ve worked with in the past? If yes, how so?

The smell of sandalwood takes me back to the memories of my olfactory study trip to Japan.

It reminds me of my discussion about perfume with a geiko (a woman of art), during a spectacular meal in Kyoto.

Her fan was infused with the scent of those traditional short sticks of incense.

She carried no other scents.

Japanese women wore very little perfume, probably out of modesty and altruism.

Sandalwood reminds me of my trip to the island of Awaji which is known for the “Koh Shi”, literally the “masters of perfume”.

They make these sticks composed of materials with precious scents, mainly woods and spices from elsewhere such as kyara (the highest grade of aloeswood).

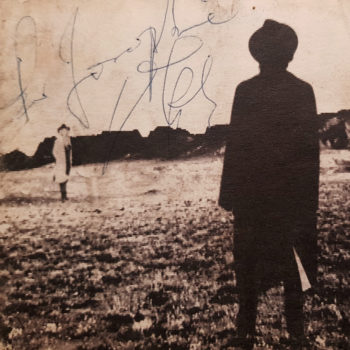

Before visiting the factories, my olfactory initiation begins at the water temple, a Buddhist sanctuary, designed by the architect, ex-boxer, Ando Tadao.

The entrance is through the roof of the building crowned with an oval pond of water lilies.

A concrete staircase guides me to a lower space, underground, where an atmosphere of tranquility pervades me.

The bright red woodwork is revealed by the light.

Barefoot, I settle in front of the censer and Buddhist icons.

I sprinkle a powder of a mixture on the charcoal and disperse with my hand the smoke and the perfume which materializes towards my nose.

The slightly pyrogenic scent is made up of sandalwood and an amber accord.

I meditate.

- What makes this material unique?

The essential oil contained in aromatic plants can also have the function of refracting light and protecting them from ultraviolet rays.

That of sandalwood harmonizes our scented compositions.

Milky or animal, it is like a second skin.

In many social and spiritual rituals, sandalwood powder protects our envelope.

It is part of the composition of the “thanaka” used in Burma or the Madagascan “masonjoany” to cover the face and defend against the sun’s rays.

This make-up is sometimes applied to the skull during prayers.

It is soothing and participates in meditation.

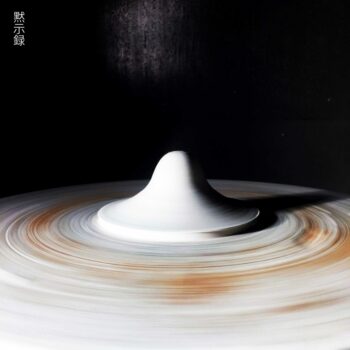

For me, the essential oil of this native Australian sandalwood is like Aboriginal body paint.

Its white color is like the color of spirits.

Aboriginal people say that drawing the sacred patterns on the chest of the child is to transfer discipline, self-respect and respect for others.

Perfume opens the mind and an olfactory education brings respect and tolerance.

My paintings are invisible.

Article P&F :

Perfumer Pierre Bénard Shares His Fragrance Notes on Australian Sandalwood

Photography : credit Dutjahn

Photography by Pierre BENARD @ Quai Branly “Paljukutjara spak in the great sand desert” by Helicopter Tjungurrayi_acrylic on canvas_1996